Soon, everyone will have a virtual personal assistant

By Peter West • 9th January 2014 18:04

Apple were optimistic when they claimed that the iPhone would become its owner's very own personal assistant. The iPhone, it was said, would simply understand your every command and help you out. It was all very impressive when it was demonstrated on stage. A guy asked his iPhone "Do I need a raincoat today? ", to which it responded: "it sure looks like rain today". But, as with most software demos, it soon transpired that it was scripted to only demonstrate the parts that work. Once it was in the public's hands, Siri struggled to understand basic questions, and was only capable of simple tasks.

Some friends and I had fun trying to find out what Siri got right. "Call me a cab," we asked it. "You want me to call you Cat?", Siri responded. It's all laughs when you don't depend on it. Sure, call me Cat, why not? What's the worst that can happen? Siri was, however, able to tell us the weather in Paris and where the nearest restaurants were. But this isn't quite the "intelligent assistant" that Apple were advertising.

There will be a time where we need to take these intelligent assistants more seriously. As much as we might try to pass them off as gimmicks and marketing buzz, experts claim that they're here to stay, and they will become more pervasive and more important to us. But for that to happen, Siri, and others like it, need to actually work.

Phones, Satnavs and cars have for years been trying to get us to say what we want to do. But they faltered on the most basic tasks. Five years ago, I could try to use voice commands to call friends on my phone (a Nokia 5800), but it required me to be in a silent room - what if I needed it when walking in town? Microsoft have had their speech recognition software completely fail on stage.

Perhaps this is forgiveable - maybe we shouldn't expect AI to be that intelligent yet. Voice recognition, then, should be kept for the simplest of tasks - dialling friends or controlling the radio while driving, or even for children to talk to their dolls.

And yet, there are constant efforts to make a computer that can respond to anything we ask, instead of simple commands that must adhere to specific syntax. Is this a pipe dream? Could we ever actually achieve a intelligent assistant that we can communicate with on a human level?

Apple has tried to do just that. "For decades, technologists have teased us with this dream that you're going to be able to talk to technology and it will do things for us... But it never comes true!" Senior Vice President, Phil Schiller, said at the Apple Special Event. "What we really want to do is just talk to our device." Schiller went on to explain that iPhone would deliver this in the form of an intelligent assistant called Siri. It would recognise our voice and then can accomplish any task we could reasonably expect a computer to be able to accomplish. This was all to huge applause - people wanted this product.

Why all the hype? What's there to gain from devices understanding our speech?

Maybe we're after a way to communicate with technology in a more human way. A human interface to the vast knowledge base that technology harbours. As Kieran Bourke of mobile marketing company Mobext puts it, it's "the beginning of the end of touch-based interactively with its limitations of thumb size buttons and grease-laden glass fronts."

But it can be more than just a convenience for some - it can be life-changing. Dr Mike Wald, a speech recognition researcher at Southampton University, says it helps in "supporting disabled users to express themselves". He explains how it could be extremely helpful for those who are unable to type. He also explains its application for deaf people, who would be able to use it to understand speech.

There's a big demand for speech recognition, but it isn't ready yet. It's ahead of its time, struggling with the complexities of language and culture.

There are two parts to speech recognition, each with its own problems to overcome. The first part is responsible for recognising voice and converting it to text. This part has to deal with different voices and accents. The second part makes sense of the words and works out what the person actually means. There are different meanings for words in different cultures. "Speech Recognition cannot just use the sounds to work out which spelling of road/road/rowed should be used ... as they all sound the same," explains Wald. He gives an example phrase which, to a computer, would be confusing to understand: "'I rode the horse along the road to the lake where I rowed a boat'".

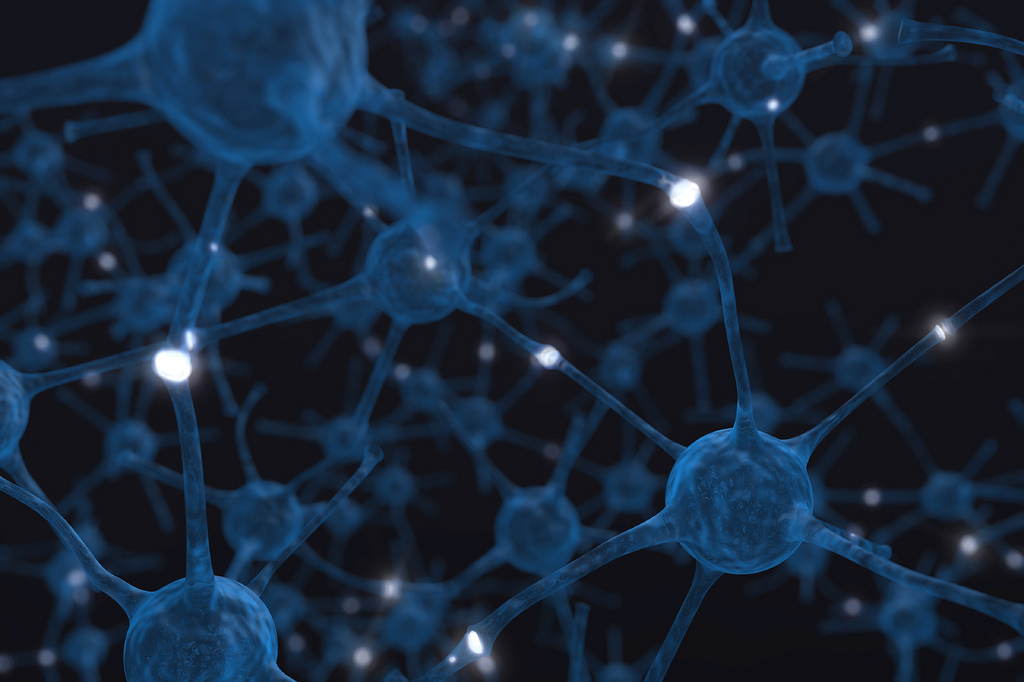

Dealing with complexities requires complex algorithms and enormous computer power. The algorithms are difficult to tweak to understand everyone, so are limited in their capabilities. But Wald suggests there's an alternative solution - "multi-level neural networks (e.g. 'Deep Belief') should produce significant improvements".

Neural Networks are simulations of human neurons in the brain. Research here goes back to the 1940's, when neurophysiologist Warren McCulloch and mathematician Walter Pitts demonstrated how neurons might work using electrical circuits. The idea of simulating neurons of the human brain to understand speech seems appropriate - neurons are great at making sense of patterns, so are perfect for understanding speech. Could Neural Networks be the answer?

"Neural Networks were being investigated for speech recognition many years ago", says Wald, "but it is only recently that computers got powerful enough to enable this to be used in real time."

Researchers began experimenting with neural networks for speech recognition as early as the 1980s. But computers were not powerful enough to scale neural networks to the complexity that was required to understand speech. Today, however, we have the necessary power. "Successful results for using Neural Networks for real time speech recognition only started to be reported last year", says Wald, "and Google were the first to incorporate them in their mobile speech recognition".

Google claim that super-human speech recognition is possible through use of neural networks. "Speech recognition is not at human performance yet" explains Google's Vincent Vanhoucke in a Tech Talk. "The problem is that it's getting dangerously close." He explains that through removing humans as a benchmark of good speech recognition, devices will reach super-human performance.

With these predictions, it is reasonable to expect that in the near future, personal assistants will better understand us and will become more popular. Soon, everyone will have their own software-based personal assistant.

Is this leading the way for a post-human future? Could we form human-relationships with devices? This idea has recently been captured in an upcoming film - Her - in which a man falls in love with his phone's operating system.

Is it possible for people to be fooled into thinking that their virtual assistant is a real human? "I think this might be possible for some people and situations", says Wald, "but I don't think it will be ethically allowed for a company to sell technology that pretends it is a real human being".

So perhaps Apple weren't so wrong in their predictions for Siri. Maybe it will become that assistant with the power of technology, but with a human-nature. "This might all seem a little far-fetched today," says Bourke, "but we are very close to a future where we will feel very comfortable engaging our devices in a conversation without feeling insane doing so. "

And what of Her? Will people be falling head-over-heels in love with their phones?

Wald says "Of course some people might 'fall in love' with technology."